Days 12 and 13 More Politics

On Thursday, our 12th day on the trip, I could have done anything I wanted, like shopping, walking in the Old City, laying around by the pool. So of course I opted for a tour along the "Security Fence" in the Jerusalem area, including Har Homa and Gilo, led by Amos Gil. He's the executive director of Ir Amin, the ACLU of Israel which works for Israeli-Palestinian coexistence.

One has to start with remembering that before 1967, anything now known as East Jerusalem was part of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan. During the war, Israel was attacked by several of its neighbors, including Egypt and Syria. It repelled the attacks, and held on to the Sinai, the Gaza Strip and the West Bank, supposedly as bargaining chips to barter peace with its neighbors.

After the '67 war, the municipality of Jerusalem annexed territory east of its boundaries that essentially doubled the physical size of the city, which means 1) the mostly undeveloped areas east of the Old City are being developed as Jewish neighborhoods, and 2) the Palestinian villages that were already there east of the Old City were annexed into Israel, and they are politically separated from the West Bank. (The West Bank being the West Bank of the Jordan River, the east bank being in Jordan.) Anything east of the walls of the Old City is Occupied Territory in the eyes of the International Community, which does not officially recognize the post-1967 boundaries of Israel.

One should also remember that the Separation Barrier is in some places a 25 foot wall, in other places just a fence that's nearly invisible from a distance, and in other places competely nonexistant except as a proposal. In all places where it is built, there are alarms and movement sensors that will bring IDF troops by the dozen in a matter of moments, anywhere along the perimeter.

Also, Ir Amin may try to litigate against the building of the barrier in certain neighborhoods, but may only do so in small segments. The barrier may not be legally challenged as a whole in Israel's courts.

We started the tour at the southermost tip of East Jerusalem. From a sidewalk in an Israeli neighborhood called Gilo, we can see the Arab town of Bethlehem in the near distance, and immediately across a small gorge is the hill village of Beit Jala. Beit Jala is one of the areas from which suicide bombers were known to come from during the Second Intifada. Both Gilo and Beit Jala are on hills facing each other. Snipers used to fire from Beit Jala onto the sidewalks of Gilo, and the Israeli army shot back from Gilo. The apartments in Gilo (which are rather nice, by the way) have bullet proof glass on their southern windows, and cement barriers on the southern side of their sidewalks. There is a separation wall, so called, between these neighborhoods, but it's in the gorge. In other words, it might prevent the crossing of suicide bombers into Jerusalem, but it doesn't help at all with munitions fire.

And about these settlements: the funding does not mostly come from the State of Israel. It comes from highly conservative American Jews, who funnel the money through some kind of umbrella organisation into Israel, buy up properties, fund real estate developments, and subsidize housing costs. For poorer Israelis, it's an economic boost.

(Conversely, I've heard of a Palestinian movement to move westward into Jerusalem as well, to plant Arabs in Jewish areas. In other words, in the urban populated area of modern Jerusalem, there's been substantial permeability in the geographical boundaries of Jewish Israelis and Arabs.)

From Gilo we move up to As Sawahira ash Sharquiya. If I remember Amos' talk correctly, this was one of the largest Palestinian villages, maybe 30,000 residents. As residents of an annexed territory, they are legally Jeruslamites, residents (but not citizens, because they refused) of Israel. When the Separation Fence was built, the village was divided such that 1/3 of the village is on the Israeli side of the wall, but 2/3 are on the side of the West Bank. That is, 2/3 of the residents of this Jerusalem neighborhood are prevented from entering into the city except through checkpoints. The nearest checkpoint is almost two kilometers north. This village/neighborhood was another political hot spot. Most Palistinian protests rallied at the very spot where the wall was built.

There is an economic implication here. Jerusalemites can earn in Shekels, in Israeli money. Arab residents are allowed to work in Israel, although it would be hard for them to live outside of East Jerusalem. They earn less, to be sure, but before the Wall they could take that money to the West Bank and spend it where everything costs a fraction of what it does in Israel. These days, they either cannot get into Israel to hold a job, or they cannot spend their lesser earnings in a place where the money will buy more. So As Sawahira ash Sharquiya is poorer now than before the wall was built.

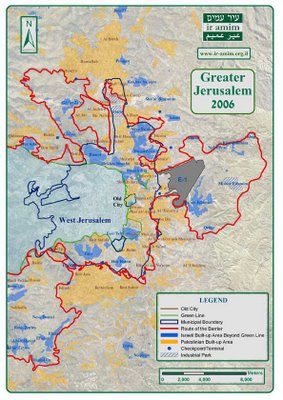

From As Sawahira ash Sharquiya we passed over the eastern side of the Mount of Olives east of the Old City, which few tourists see. Directly below us is the village of Az Za'ayyum. In the distance on the left is an area know as E-1. Beyond Az Za'ayyum to the west and a bit south is Ma'ale Edumim, a large Israeli settlement that's really the largest suburb of modern Jerusalem, tens of thousands of people. And this is where things get complicated.

From As Sawahira ash Sharquiya we passed over the eastern side of the Mount of Olives east of the Old City, which few tourists see. Directly below us is the village of Az Za'ayyum. In the distance on the left is an area know as E-1. Beyond Az Za'ayyum to the west and a bit south is Ma'ale Edumim, a large Israeli settlement that's really the largest suburb of modern Jerusalem, tens of thousands of people. And this is where things get complicated.Most residents of Ma'ale Edumim are not there for idealogical reasons specifically. They may be Zionists who believe in the State of Israel, but they're not zealots. It really is a suburb, full of middle class people. It's unlike settlements farther out, which are basically frontier towns of armed ultra-Orthodox settlers living in little fortresses. Ma'ale Edumim is more like Walnut Creek.

It is, however, east of the municipal boundaries of Jerusalem, and without doubt well into the Occupied Territories. The Separation Barrier is planned to be built in a kind of bubble extending about 10 km east of the new municipality of Jerusalem, into a mostly undeveloped desert area about the size of Tel Aviv. It would swallow Az Za'ayyum. More than that, the Barrier would butt up to a mountain range that extends to the Jordan River Valley, which is controlled by Israel. In effect, it would divide the West Bank into two geographic regions, north and south of the mountains. According to Amos, when most Israelis discuss a separation wall around Ma'ale Edumim, they do not understand that the proposed wall extends much farther than just this suburb.

If you refer to the map above, you can see that E-1 is a kind of cork between this proposed bubble extension of the barrier to the east (including Ma'ale Edumim and Az Za'ayyum), and Jerusalem to the west. E-1 is a proposed police station surrounded by a kind of no-man's-land. This police station is also funded by American money.

So suppose Israel ever gets around to considering giving the West Bank to an independent Palestinian state. Does Ma'ale Edumim, a mere 2 km from Jerusalem, remain in Israel or go to Palestine? If it stays in Israel, what about Az Za'ayyum, which lies between Ma'ale Edumim, E-1, and Jerusalem? What about the hundreds of thousands of people living within the current municipal borders of East Jerusalem, in Gilo, East Talpiyot, French Hill, and Ramot? They technically live in West Bank, but it would be like giving the Simi Valley back to Mexico while keeping West LA and Santa Monica for California.

(Note that I'm not saying they should have been there in the first place. It's just an acknowledgement of how the situation stands right now.)

The realization for me is that even if a two state solution were reached, and a truly independent Palestine created, I don't see how Palestine is going to get back everything that was taken as the West Bank. It's not a matter of whether I'd want them to; it's more like I think they'll get a raw deal out of it, and it's possible that the borders of Palestine will not knock on the gates of Jerusalem itself. Yet Jerusalem is the nominal capitol of Palestine as well as Israel, and contains the third most holy site of Islam, the Dome of the Rock.

Amos Gil was a very informative guide, and tried his best to present all sides of the situation, inserting as little of his views as possible. His goal, which I think he accomplished, was "to make you confused," and to demonstrate the complexity and intractibility of Jerusalem as a specific case problem in Israeli-Palestinian relations.

The next morning we got up to listen to a talk by Professor Yaron Ezrahi, the expert on Arab-Israeli relations at Hebrew University. It was a privelege to be addressed by this man, who is the most sought after commentator on this topic in the country. He had several extremely interesting points to make, and I will try to represent them as closely as I remember. Just try to remember that these are his ideas.

The first relates to my question to Dan Yakir of Ir Amin. Since Macchievelli, it's been a widely held tenet of international relations that people may judge governments by moral standards, but governments would never stay in power if they truly adhered to those standards. So the trick (and the US was very good at this until recently) is to appear to uphold moral values while nevertheless acting for "reasons of state". But with the globalization of media, and the ability for the world's citizens to communicate electronically, morality itself has become a "reason" the state should act on. A state in poor moral standing will not have the political cachet to act effectively. For example, the United States has such dismal moral standing in the Middle East that it cannot effectively intervene between Lebanon and Israel.

Second, the occupation of the West Bank is not only Israel's greatest sin (his word), but its greatest strategic error in working for a secure Israel. It's a sin that costs Israel dearly in its moral standing with its neighbors, and therefore makes friendly relations impossible. And furthermore, the Israeli army is highly trained in the methods of policing and occupation, so much so that when it comes to defending Israel against real armies (like the Hezbollah militia), the army is undertrained, thus further threatening the security of the state. But whenever Jewish settlers set up a development within the Territories, it has always been the policy of the state to spend huge amounts of army resources protecting those citizens, whether they're officially authorized to be somewhere or not.

(This is in contrast, again, to the United States, whose army is extremely well trained and equipped for small military incursions, but which is utterly unable to police an occupied territory the size of Iraq in a way that prohibits violence.)

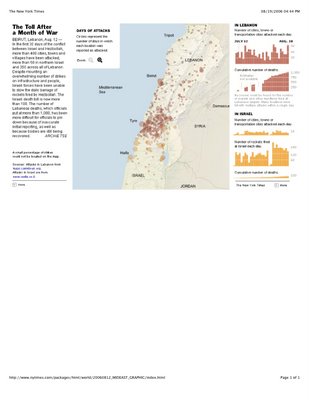

So about Lebanon. In his view, Lebanon is a government on paper only. It is not a sovereign state, in the sense that the Lebanese government does not have a monopoly on the use of force within its borders. In fact, Hezbollah is probably one of the strongest armies in the Middle East, and not controlled by any official state.

Ezrahi is not a pacifist or a leftist, he strongly felt Israel has the duty to protect its borders and its citizenry. He's a Zionist who in general supports the state of Israel. But following Hezbollah's invasive sortie, bombing the hell out of Lebanon was not the best strategic way to do this, especially as regards the moral/political cachet of Israel. He felt that a better way would have been to give one month in the attempt to negotiate the release of the Israeli soldiers taken by Hezbollah.

On the assumption that negotiations will fail (and I'm afraid I agree it would have been a good assumption), Israel should have trained up its ground troops for guerilla operations. Ezrahi's idea is to send in the ground troops first, with air force as back up, and be highly targeted in military operation against enemy militia, avoiding civilian casualties as much as possible to protect Israel's moral standing as much as possible.

But that's not what Israel did and it lost its moral, and therefore political, good standing. There's been a groundswell of support for Hezbollah throughout the Arab world. The best case outcome, as Ezrahi sees it, is that Hezbollah takes over Lebanon in democratic elections, and that its militia is incorporated into the official armies of the state.

That's the best case. The most likely case, as he sees it, is that Lebanon will plunge into civil war, and Hezbollah will take over the state by use of force and depose the current government. Lebanon cannot withstand the Hezbollah militia.

In terms establishing a lasting ceasefire with Israel, a Lebanese army would not be strong enough to police a no-fire zone between the two states. Further, Hezbollah militiamen, he says, can and do easily change out of the Islamist militia uniform and into the uniform of the Lebanese army; and that doesn't help Israel at all. Neither could the United States intervene directly, because it has neither the moral standing with the Arab world, nor can it spare the military resources which are tied up in Afghanistan and Iraq. So it becomes a matter of whether the United Nations can muster a sufficient peacekeeping force or not. Otherwise, the state of Israel may be tempted to simply take over Lebanon altogether, which would be diplomatic disaster.

So altogether not a very rosie view, but a compelling and nuanced view from a moderate Israeli. I did my best to portray his view accurately.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home